A few readers asked me to expand on the tips I offered in the last post on Stories from a Recent Depression [1]. I will do that a little further down in this post. Before we get there, there are two “D-Watch” [2] issues I’d like to bring up, one from long ago, one more recent.

A few readers asked me to expand on the tips I offered in the last post on Stories from a Recent Depression [1]. I will do that a little further down in this post. Before we get there, there are two “D-Watch” [2] issues I’d like to bring up, one from long ago, one more recent.

Meet Severus, Defender Against the Dark Arts

Actually the Severus most important to modern finance is not Severus Snape [3] from J.K. Rowling’s [4] extensive Harry Potter [5] series, but Alexander Severus [6], Roman Emperor from 222-235 A.D., whose death touched off the Crisis of the Third Century [7] and near collapse of the Roman Empire. If only only Alexander Severus been able to conjure a Patronus Charm [8]!

Let’s sum up, Severus [9] was born in 208 A.D. When he became Emperor in 222 he inherited a growing and prosperous Empire. A military defeat, graft (bribing the Germanic invaders), economic over-expansion and low morale led to a plot by Severus’ troops to murder him in 235.

Let’s sum up, Severus [9] was born in 208 A.D. When he became Emperor in 222 he inherited a growing and prosperous Empire. A military defeat, graft (bribing the Germanic invaders), economic over-expansion and low morale led to a plot by Severus’ troops to murder him in 235.

After Severus death, the Roman Empire suffered economically from hyperinflation. The solutions of the Crisis of the Third Century [7] were counter productive. The Empire saw increased taxation, abandonment of property (to avoid taxation), crumbling infrastructure and collapsing trade. It was not until the ascension of the Emperor Diocletian [10] in 284 that the Crisis finally abated.

I. Ruina Ab Imperium (Collapse of Empire)

Scholars have written encyclopedia volumes on the causes and effects of the Crisis of the Third Century, but a short list relevant to readers of Global Finance Net is this:

- Overexpansion of military commitments (many of which were not decisively winnable).

- Overexpansion of debt (trade credits and early Roman mortgages).

- Failure to maintain infrastructure necessary for commerce.

- Inefficient use of resources (use conquered assets to support Imperial lifestyles while producing very little).

- Severe persecution of religious minorities.

So what happened during the Crisis and even in the time between the end of the Crisis and the eventual fall of the Roman Empire in 467?

- Hyperinflation

- Devaluation of the currency

- Collapse of trade

- Ruin of infrastructure

- Price controls

- Government instability

- Rise of competing social and religious ideology (remember that Christianity was a radical religious idea back then).

II. More Recent Signs from “D-Watch”

I’ve decided to start a depression watch or “D-Watch” given the recent main stream media (MSM) [11] penchant for scare stories about the Great Depression [12] in the U.S. First, here is a short list of MSM articles that make our D-Watch list for today:

- CNN Money: The Big Three Depression Risk [13].

- The Australian: Depression Risk Hits Shares [14].

- Laurel Leader Call: The Children of Depression 2.0 [15].

Aside from the macabre thrill of keeping tally of our new global D-Watch pastime, my opinion remains that all comparisons to 1929 (or corrected to 1931 or 1933) are worthless. First, few economists and financial advisors know what they are talking about [16] and I guarantee that none of them can predict the future [17].

That said, it is better to use reason and induction to at least come up with theories or scenarios of what might happen. We should focus on simple things where we can see what is happening.

III. D-Watch Central Chart

Most of the U.S. market downturn can be summed up in one word – debt. The fact is that the U.S. is faced with a problem similar to that which led to the Crisis of the Third Century and that is our debts far exceed our ability to produce our way out of them. Forget repayment, given an infinite time horizon, all debts can be repaid. The problem is that we don’t have infinite time and we don’t want our production deflated by the burden of crushing debt.

One chart making the rounds on the Internet is the U.S. Total Credit Market Debt to U.S. GDP from Hayman Advisors. See for yourself (from Clusterstock [18]):

The chart illustrates one very simple possibility for the markets in the U.S. – we are heading back to levels not seen since the mid-1980s because of the need for a reduction back to a 150% debt burden. Obviously, there are a lot of details behind this simplistic conclusion. Who holds the debt? How long will it take to unwind? Who declares bankruptcy? And so on . . .

We can put the debt chart with our Dow history charts from the earlier Charts to Show That Markets Don’t Always Go UP! [19] post. The Great Depression debt bubble lasted between roughly 1928 and 1941. Our Dow Jones chart for the period [20] shows that the average settled around 175 after falling from the 1929 high of 381, a 54% loss. Likewise, we see that the debt ratio reduction was from 260% to around 135% (though it vacillated back to the 160% level, probably due to WWII). Put the two together, a 50% loss in the market from peak matched a 50% deleveraging relative to GDP.

IV. D-Watch Doesn’t Make Sense Without GDP [21] Contraction, Debt Increase or Both

Now let’s take a look at our 1968-2008 Dow chart [22]. If we assume that deleveraging should go to the 150% debt/GDP point (roughly back where we were in 1985), then the equivalent chart point for the Dow is the 1985 range of 1,500. This would imply a drop of 80% from today’s level of about 7,500 (to speak nothing of last Fall’s 14,000 highs). The deleveraging reduction from 360% to 150% is a 58% reduction, so the math doesn’t quite take us back to the mid-1980s, so we should probably assume one of the following:

- The deleveraging will take us down another 60% (though markets always overshoot), so the 1992 level of 3,000 is more likely.

- The ratio is worse than we think, say 400%, or we will have to have to deleverage more, say to 75% in today’s numbers.

This is probably the most realistic driver of an 80% change, and the driver is what wakes me up in the middle of the night, GDP contraction [23]. Depending on the degree of denominator compression (that is the top number – debt – stays fixed or grows, the bottom number shrinks), we could get to a 400% debt/GDP ratio. Let’s assume a 10% GDP contraction [24] drops 2009 GDP from $14.3 trillion to $12.9 trillion, let’s also assume debt doesn’t increase. Our new ratio would be 395% and reducing to 150% is a larger reduction.

Could this happen? We’ve laid out the assumptions above and believing that both GDP will contract while debt increases is probably reasonable. Believing that this will negatively impact the market is probably also reasonable. The question is one of when and how much and this is where fortunes will be made and lost.

V. Guide to D-Watch

I promised some tips for what to do and here they are. First is to think and analyze. One article I cited above noted the end of financial experts [16]. I don’t think advice or expertise is going away, I’m certainly not anti-intellectual. I do think that people will become more discerning after both the dot-com bust and this crisis, we will all need to know the difference between real advice and “the stopped watch is right at least two times a day.”

Second is a group of things I experienced in Russia during the 1990s. As I said in the last Stories from a Recent Depression [1], I think more recent economic crises hold better lessons than 1929.

- Family, friend and community networks are critical. In Russia, currencies were cancelled with only a weekend notice, controlled prices were freed in the same chaotic fashion, banks and ATMs stopped working literally overnight. If you can’t use cash or credit cards (and stop telling me about gold, silver, conspiracy, blah, …) you have to rely on connections, goodwill and so on.

- Seek out local products. At the end on the 1990s much of Russia’s goods were imports. At the beginning of 2000, most goods were domestically produced, foreign goods were unaffordable to the average Russian. The same will happen in the U.S. and E.U. eventually. Do an experiment, next time at the store, see if you can shop and exclusively within your continent (North America or Europe). See what has to be imported and what can locally replace it.

- Drop the silly fads and happy talk to focus on the situation at hand. I’ll do a post on this later, but the whole “it’s cool to be frugal” is, let me say, stupid. It is not cool, not when people starve, not when the sick can’t get healthcare, not when families are bankrupted, not when resources are pillaged, not when companies are destroyed and not while the looters of our economy go unaccounted. No it’s not cool at all and I think we will all be better off when there is some real wealth, even if we have to redistribute it to be fair [25].

- Build your personal value, think about what will be needed if the economy gets really bad. Will your skills as a real estate agent or mortgage broker be highly valuable? Probably not. What about skilled plumbers, computer repair, sewing clothes, medical work, growing and preparing foods? Someone might need this.

- Finally, get your health and life in order. If things go bad, you will need this above all else, those who survive are those most adaptable to change [26]. And above all, remember that the “market” is a fiction, it does not feel, think or relate. What matters most is your friends, your family and your love.

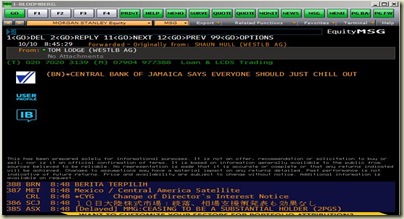

The Central Bank of Jamaica seems to have the right attitude (from The Big Picture [27]):

. . . And that’s how it goes